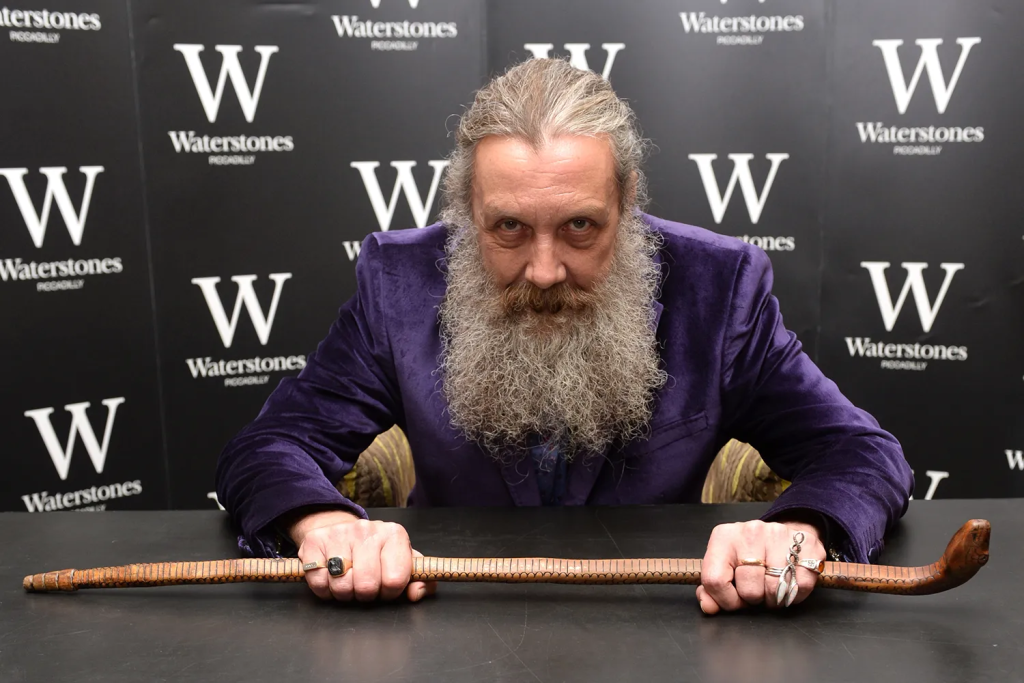

From a review of author/magician Alan Moore’s very long-awaited grimoire, The Moon and Serpent Bumper Book of Magic:

Magic, for the Moores, is somewhere between metaphor and spiritual practice. It’s a way, like art, of exploring the rich territory of internal worlds, following the maps offered by tools like kabbalah and the tarot, and shaping that personal internal world in a way that influences the collective imagination. Fictions can shade into reality. Gods and demons are created out of the human psyche, but that doesn’t make them less influential or powerful. For Alan Moore, for instance, that happened when his tale of a revolutionary wearing a Guy Fawkes mask, V for Vendetta, led that mask to become a symbol of global protest.

But the authors are aware of how blurry the lines are around the histories they relate—and how the fiction can be more important. The magician whose history is related at the greatest length is Alexander of Abonoteichus, a second-century charlatan and the creator of the snake god that Alan Moore himself worships, Glycon, who in real life was a drugged python in a blonde wig. Alexander’s life is told in a series of Mad magazine-style comic strips that dub him the “quack with the knack” and the “fake with the snake.”

For Alan Moore, as he described at length in one story, Glycon’s great advantage as a god is that he is verifiably false. As he has “Glycon” say, “This is the only way gods manifest, in paint, and props, and poetry. I am not the docile python, or the false head, or the borrowed voice. I am the idea that generates these things.”

We live in an age dominated by angry ideas and pervasive fictions. The Moon and Serpent is about creating ideas that blur into reality, but as Alan Moore has remarked, “The big advantage of worshipping an actual glove puppet, of course, is that if things start to get unruly or out of hand, you can always put them back in the box.”