Selected passages from Edgar Morin’s Homeland Earth : A Manifesto for the New Millennium (1999):

I would expand the line from Hölderlin by saying: We dwell on Earth both prosaically and poetically. Prosaically (when we work, aim at practical targets, try to survive), and poetically (when we sing, dream, enjoy and love, admire).

Human life is prose and poetry woven together. Poetry is not only a literary genre but also a way of life involving participation, love, fervour, communion, enthusiasm, ritual, feasting, intoxication, dance, and song, which in effect transfigures prosaic life made of practical, utilitarian, and technical chores. Furthermore, each and every human being speaks two languages with its mother tongue. The first denotes and objectivizes and is based on the law of the excluded middle. The second rather speaks through connotation, which is the halo of contextual significations surrounding every word or phrase, toys with analogy and metaphor, tries to translate emotions and sentiments, and allows the soul to manifest itself. Two states, often separate, are also present in us, the first or prosaic one answers to rational/empirical activities, and the state rightly called “second”–the poetic state–is brought about not only by poetry, but also by music, dance, festivity, joy, and love and reaches its highest point in ecstasy. When in the poetic state, the second state is the first.

Fernando Pessoa used to say that there are two beings in each of us. The first, the true one, is the one of visions and dreams, born during childhood and lasting throughout life; the second, the false one, is the one made of externals, of words and actions. We can put it this way: Within us, two beings reside, the one prosaic, the other poetical. These two beings or states make up our being, they are its two mutually indispensable polarities. Prose in particular is a prerequisite of poetry, and the poetic state as such cannot appear except on the backdrop of the prosaic state.

The prosaic state sets up for us a utilitarian and functional situation with its goal being utilitarian and functional.

The poetic state can be linked to loving or brotherly/sisterly goals, but it is also an end in itself.

The two states may oppose each other, exist side by side, or mix-together. In archaic societies, they interacted closely; daily work, the grinding of flour, for instance, was accompanied by songs and marked with rhythm. The preparation for hunting or war involved mimetic rituals made of songs and dances. Traditional civilizations hinged on the alternation between festivities–when taboos were lifted and when enthusiasm, spending, intoxication, and destruction prevailed–and daily life, burdened with constraints and bound by frugality and parsimony.

Modern Western civilization has separated prose and poetry. It has made festivities scarce and to some extent drained them to the benefit of leisure, a catch-all notion that everyone fills as best they can. The life of work and economic activity has been invaded by prose (the logic of profit, etc.)* [*There are, of course, poetic delights enjoyed by capitalists, managers, and so on, that are based on the will-to-wealth and profit, on the exercise of leadership in enterprise, stock market speculations, etc..]; poetry has been relegated to private life, to leisure and vacations, and it has evolved in its own way through love affairs, games, sports, movies, and of course literature and poetry proper.**

[** Literary poetry has revolted twice against prosaic, utilitarian and bourgeois life: first, in the early 19th century, with Romanticism, especially its original German variety, and second, in Surrealism, which, like Romanticism but more explicitly, signified poetry’s protest against being reduced to literary expression pure and simple, and most of all its will to be incorporated into life. Surrealism wanted to continue Arthur Rimbaud’s attempt at deprosifying daily life in order to unveil the wonders that lie hidden in the dirtiest or Iowliest aspects of ev[eryday existence.] Today, at the turn of the millennium, hyperprose has made progress through the logic of artificial machines which has invaded all spheres of existence, through the hypertrophy of the technobureaucratic world and the spread of clock time, both overloaded and strained, at the expense of the natural time of living beings. The betrayal and collapse of the poetic hope in a universal victory of fellowship has spread a blanket of prose over the world. On the ruins of the poetical promise to change life, ethnic and religious revivals endeavor to reclaim the poetics of communal participation, while the prose of econocratism and technocratism, which turns politics into management, is triumphant in the Western world, no doubt only for a time, but for now at any rate. Granted that politics need not take upon itself the dream of doing away with world prose through the realization of earthly happiness, it does not follow that it should shut itself up in prose. This amounts to saying that the politics of humanity does not have as its sole target advanced industrial society, postindustrial society, or technical progress: The politics of development, in the sense discussed previously as inclusive of the idea of metadevelopment (see Chapter 4), involves the full awareness of humanity’s poetical needs.

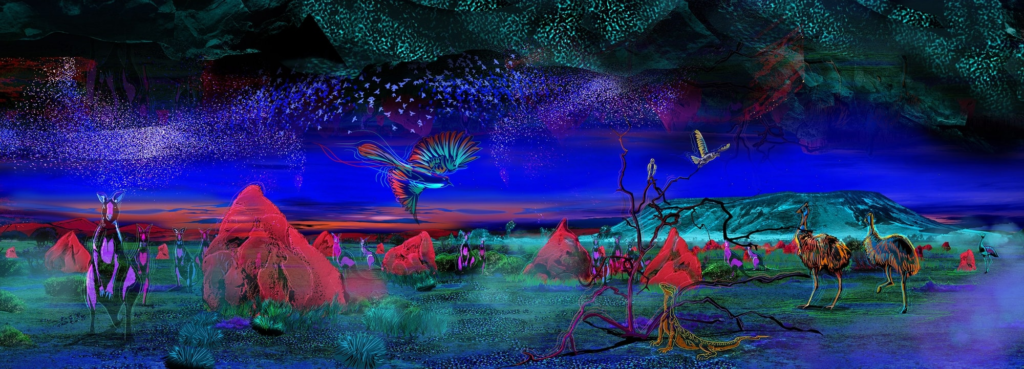

Such being the case, the spread of hyperprose calls for a powerful counteroffensive of poetry, which must go hand in hand with the revival of fellowship and the gospel of doom [that is, the earthbound religion of “re-liance” discussed elsewhere]. As a matter of fact, awareness of Homeland Earth can by itself put us in a poetic state. The relation to Earth is esthetic, better still, Ioving, and sometimes ecstatic. How not to sway in ecstasy when, all of a sudden, a huge moon flashes unexpectedly on the threshold of night? How not almost to swoon at the sight of flying swallows? Are they only marvelous flying machines; do they cry uniquely in order to convey information? Are they not delighted and maddeningly thrilled by their swift turns and dives, their climbing skyward, brushing past yet never touching each other?

To reiterate, it is useless to envisage a permanent poetic state which, in any case, if uninterrupted, would fade on its own or become haggard. We would be reviving in a different way the illusions of this-worldly salvation. We must abide by complementarity and the alternation of poetry and prose.

We have a vital need for prose because practical, prosaic activities help us survive. Already in the animal kingdom, survival activities (looking for food or prey, defending against dangers or aggressors) often fill the whole of life and preclude enjoyment. Today, on Earth, humans spend most of their lives surviving.

We must strive to make the second state be the first. We must try to live for the sake of living and not only for sheer survival. Poetic life is precisely that: life for life’s sake.

See also: