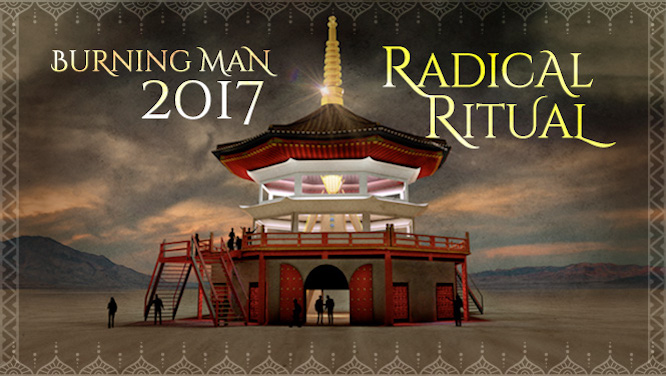

In 2017, Burning Man’s theme was “Radical Ritual,” and the Burning Man Philosophical Center project produced a series of essays and interviews exploring the place of ritual in modern society.

Here’s a section from Larry Harvey’s introductory essay:

Is Burning Man a Religion?

“The practical needs and experiences of religion seem to me sufficiently met by the belief that beyond each man and in a fashion continuous with him there exists a larger power which is friendly to him and to his ideals. All that the facts require is that the power should be both other and larger than our conscious selves. Anything larger will do, if only it be large enough to trust for the next step.”

—William James, Varieties of Religious Experience

There are two basic views of divinity. The first sees the divine as transcendent; the other views the divine as immanent. Transcendence is from the Latin word transcendentem: it means surmounting, rising above, as if to step up on a ladder. Immanence derives from the Latin immanere and evokes the feeling of an indwelling presence. It refers to all that is inherent in our being. For all practical purposes, the rituals I have described support these feelings and perceptions — they are very nearly textbook examples of religious experience.

The only thing that this leaves out is supernatural agency, an external power that is said to hover over us and inform our deepest feeling of reality. William James has said that, “All the facts require is that this power be both other and larger that our conscious selves. Anything larger will do”, he adds, “if only it be large enough to trust for the next step.” The Man we’ve made, of course, is not a god, nor is the burning of the Temple evidence of supernaturalism. Energy did not flow from the Man into a group of followers. Rather it was their energy, their full-hearted participation that created the Man. When people joined in chorus round the Temple, it was their voiced spirit, and not divine afflatus, that united them.

Were we to remove all soul and all spirit from experience, we would be left with little more than what William James once called, “a cold and a neutral state of intellectual perception.” In such an arid landscape, there would be no urgent meanings, no riveting purposes, and the juice of reality would be squeezed out of the world.

Sometimes I am asked to speak in churches. Many people in religious communities seem to feel we might be onto something. I approach them with a proposition. “What if we gathered people of all faiths,” I say, “and, placing them in a locked room, demanded they settle a question: Which Supreme Being, of all the millions of supremely potent beings mankind has worshiped, is really real?” I pause for a moment to let this sink in, and then continue, “Were we to leave and come back a day later, I am willing to wager that we’d find only hanks of hair and pieces of bone — so fierce would be the force of contradiction. Yet what if we here, now, were to reverse this word order and agree to simply say that being is supreme?” Then I see their eyes begin to faintly glint, their shoulders soften, and some people heave a little sigh of relief.